Beyond the Urban-Rural Divide: What the Wheatears 2030 Camp Teaches Us About Educational Innovation

By Yuyan Wang, Associate Program Officer, UNESCO/Chief Consultant, SEESALT Terra

This summer, something interesting is happening in Zhuzhou, Hunan Province. The Wheatears 2030 Summer Camp—a joint initiative between SEESALT and MOVO China—is bringing together 11-15 year old students from cities with their peers from urban-rural transitional areas, along with international students from elite schools like Harrow and Winchester College. On the surface, it looks like another cross-cultural educational program. But dig deeper, and you'll find a more complex experiment in addressing one of China's most persistent challenges.

Opening Ceremony

The Educational Borderlands

Seminar On Education Innovation-SEESALT+MOVO

Urban-rural transitional zones occupy a unique position in China's development landscape. These areas—caught between rural policies they can't access and urban resources they can't reach—have become educational "valleys" where students face a triple burden: academic pressure, cultural displacement, and limited pathways for advancement.

The camp's location at Bada Middle School in Zhuzhou isn't accidental. This school, originally founded in 1962 as a railway factory children's school, now serves 1,822 students in an area where traditional support systems have been disrupted by migration and urbanization. With over 220 students classified as "children in difficult circumstances," the school embodies the challenges facing transitional communities across China.

SEESALT-MOVO Partnership: Theory Meets Practice

Teachers at the Program

The collaboration between SEESALT and MOVO China represents an interesting convergence of development consulting expertise and grassroots educational innovation. SEESALT's experience with participatory development methodologies, combined with MOVO's deep understanding of Chinese educational contexts, creates a framework that moves beyond traditional "teaching to the countryside" models.

This partnership reflects broader trends in how international development organizations are adapting their approaches to work more collaboratively with local institutions. Rather than importing external models wholesale, the joint initiative attempts to synthesize global best practices with contextual knowledge.

Project-Based Learning Meets Social Reality

The camp's methodology deserves critical examination. By organizing students into cross-cultural action groups and using project-based learning (PBL) to address local challenges, the program attempts to operationalize some of the participatory approaches outlined in SEESALT's development toolbox.

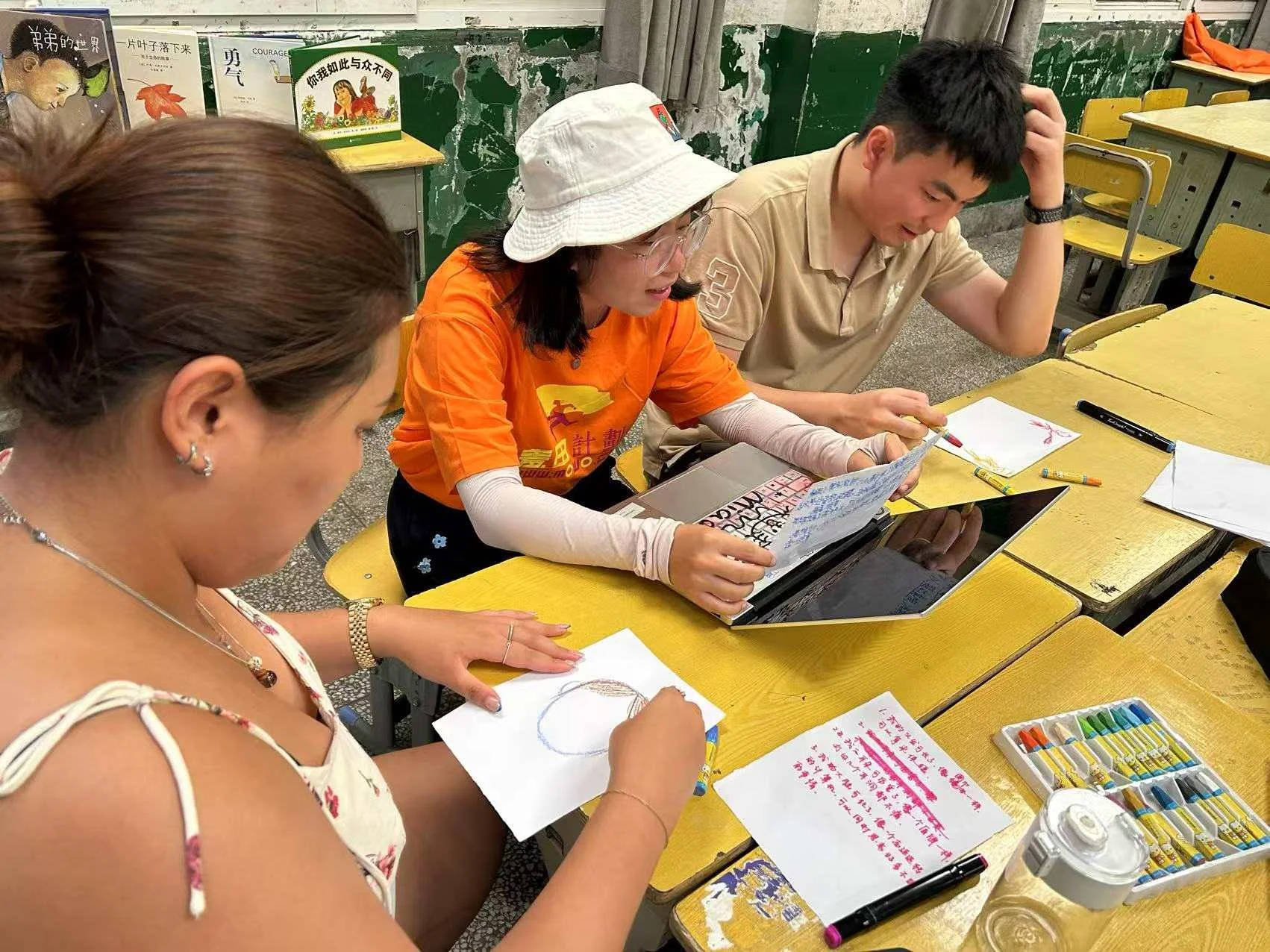

Children at our joint workshop

The curriculum framework—"field discovery, problem diagnosis, solution incubation, outcome transformation"—mirrors the stakeholder engagement and community consultation methodologies that both organizations promote in their broader work. But the real test will be whether urban students genuinely engage with the complexity of rural-urban transition challenges, or whether they approach them as problems to be solved through external intervention.

The Global-Local Tension

There's something both promising and concerning about bringing students from international elite schools into rural Chinese communities. The SEESALT-MOVO partnership frames this as exposing all participants to "multiple cultural perspectives" and fostering "global citizenship."

But whose version of global citizenship are we talking about? The risk is that international perspectives become synonymous with superior perspectives, inadvertently reinforcing the very hierarchies the program claims to challenge—a dynamic that development organizations often struggle with in their own work.

That said, the reverse dynamic could be equally valuable—urban and international students confronting the limitations of their own assumptions about development, education, and social change.

The Economics of Participation

The camp's funding model reveals tensions familiar to anyone working in development finance. Urban participants pay 5,300 yuan, which covers their own costs plus subsidizes local students' participation. This "philanthropic partnership" approach acknowledges economic inequality while creating opportunities for meaningful interaction.

But it also raises questions about power dynamics that SEESALT's own stakeholder analysis frameworks would flag. When participation is framed as urban students "sponsoring" rural students, how does that shape the relationships and learning that emerge?

Beyond Summer Camp Idealism

The most ambitious aspect of this program isn't the week-long camp itself—it's the assumption that participants will continue fundraising and advocacy work afterward. The organizers expect students to design fundraising products, develop influence strategies, and sustain engagement with rural development issues.

This expectation reflects both optimism about young people's commitment and perhaps the kind of sustainability challenges that development projects frequently face when initial funding or enthusiasm wanes.

Measuring Impact

If this SEESALT-MOVO joint initiative works, it won't be because it "empowers" rural students or "educates" urban ones. It will be because it creates genuine relationships across difference and helps all participants develop more nuanced understandings of China's development challenges.

Success would mean urban students recognizing the sophistication of rural communities rather than seeing them as problems to solve. It would mean rural students gaining confidence in their own knowledge and perspectives rather than simply absorbing external validation. And it would mean international students understanding China's development complexity rather than mapping their own frameworks onto unfamiliar contexts.

Testing Development Principles

Programs like Wheatears 2030 serve as laboratories for testing whether participatory development principles can work in educational settings. The integration of UN Sustainable Development Goals, critical pedagogy principles, and cross-cultural collaboration represents a serious attempt to innovate beyond traditional approaches.

But innovation in education is particularly difficult because it requires changing not just curriculum or methodology, but deeply embedded assumptions about knowledge, authority, and social change—challenges that mirror those facing development organizations globally.

Questions Worth Watching

As this SEESALT-MOVO experiment unfolds, several questions seem particularly important: Do cross-cultural educational programs actually challenge hierarchies, or do they reinforce them in more sophisticated ways? Can project-based learning address structural inequalities, or does it risk reducing complex social issues to technical problems with design solutions? And what does it mean to develop "global citizenship" in contexts where global and local interests may conflict?

The answers won't be clear from a single summer camp. But joint initiatives like this represent important tests of whether development methodologies can be adapted for educational innovation—and they deserve both support and critical attention.

The Wheatears 2030 Summer Camp is a joint initiative between SEESALT and MOVO China, running August 4-10, 2025 in Zhuzhou, Hunan Province. The program represents an innovative application of participatory development principles to cross-cultural education.

#SEESALT #MOVOChina #EducationalInnovation #RuralEducation #CrossCulturalLearning #China #SocialChange #ProjectBasedLearning #ParticipatorDevelopment